Comet’s coma composition varies significantly over time

“If we would have just seen a steady increase of gases as we closed in on the comet, there would be no question about heterogeneity of the nucleus,” says Dr. Myrtha Hässig, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Instead we saw spikes in water readings, and a few hours later, a spike in carbon dioxide readings. This variation could be a temperature effect or a seasonal effect, or it could point to the possibility of comet migrations in the early Solar System.”

“Our whole concept of the variability of volatile release at comets will change based on this paper, which will have significant impact on our understanding of comet formation and evolution,” says Dr. Hunter Waite, a program director and planetary scientist at SwRI.

Comets are small Solar System bodies with a nucleus composed of ice, dust, and small rocky particles. As comets approach the Sun along their orbit, they heat up and outgas, displaying visible atmospheres and tails. Comets contain some of the best-preserved material from the formation of our planetary system, offering clues about physical and chemical conditions that existed in the early Solar System.

Rosetta has been studying Comet 67P/C-G since it began approaching the four kilometre wide world last year, finally arriving at a distance of 100 km on 6 August 2014.

“From a telescope, images of a comet’s atmosphere suggest that the coma is uniform and does not vary over short periods of hours or days. That’s what we were expecting as we approached the comet,” said Dr. Stephen Fuselier, a director in the SwRI Space Science and Engineering Division and the lead U.S. co-investigator for ROSINA’s DFMS instrument. “It was certainly a surprise when we saw time variations from 200 km away. More surprising was that the composition of the coma was also varying by very large amounts. We’re taught that comets are made mostly of water ice. For this comet, the coma sometimes contains much more carbon dioxide than water vapour.”

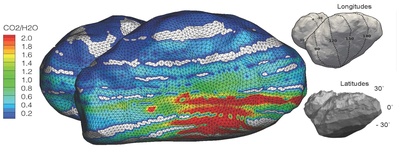

Indeed, ROSINA data indicate that the H2O signal is strongest overall; however, there are periods when the CO and CO2 rival that of H2O.

“These large fluctuations in composition in a heterogeneous coma indicate diurnal or day-night and possibly seasonal variations in the major outgassing species,” says Hässig. “When I first saw this behavior, I thought something may have been wrong, but after triple-checking the data, we believe 67P has a complex coma-nucleus relationship, with seasonal variations possibly driven by temperature differences just below the comet surface.”

The nucleus of 67P/C-G consists of two lobes of different sizes, connected by a neck region. This complex, “rubber-ducky” shape likely plays a key role in this variation, as different portions of the nucleus face the Sun during the comet’s 12.4 rotation cycle. If the coma composition reflects the composition of the nucleus, variations suggest that the nucleus may have formed by collision of smaller bodies that originated from very different regions of the early Solar System. This discovery could revolutionize theories about comet formation and the relationship between comet composition and the location of its origin.

As the comet continues its 6.5-year journey around the Sun, Rosetta scientists will be able to consider seasonal variations as well.

“Time Variability and Heterogeneity in the Coma of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko” is published in the 23 January issue of the journal Science.

The ROSINA team is led by Kathrin Altwegg of the University of Bern, Switzerland.