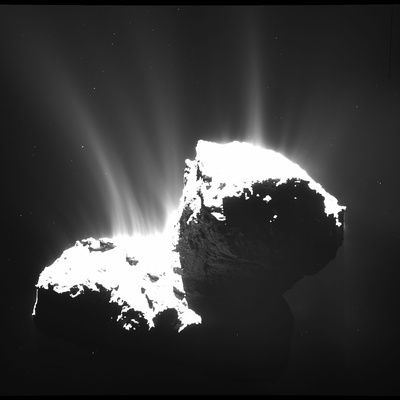

Fine structure in the comet’s jets

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has shown activity in the form of jets for many months now, but the latest image reveals that the large-scale jets seen in previous images can now be resolved into many smaller jets emerging from the surface, which seem to merge together further away from the comet nucleus. Although much activity still emanates from the ‘neck’ region, jets are also appearing from both of the comet’s two lobes.

The image presented here was taken on 22 November 2014 by the OSIRIS wide-angle camera, from a distance of 30 km. It is part of a set of observations dedicated to the investigation of the comet’s general activity. As such, the nucleus is deliberately overexposed in order to reveal faint jets and the collimated nature of the streams of gas and dust rising from the surface.

“This is still the beginning of the activity compared to what we expect to see in summer this year,” says OSIRIS principal investigator Holger Sierks from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. “From the last perihelion passage we know that the comet will evolve by a factor of 100 in activity at that time compared to now.”

But the jets are already strong enough now to show distinct features, from which the OSIRIS scientists aim to understand the physical processes that are creating and shaping them.

In this particular study, the jets were observed over one full comet rotation. “By tracking them from image to image, we reconstruct their three-dimensional structures and link them to specific areas on the nucleus, of which the morphology and composition is now being investigated,” explains OSIRIS scientist Jean-Baptiste Vincent from MPS.

By understanding where exactly the jets are emerging, e.g., from the cliffs or plains, the scientists will learn exactly how the activity is generated. The scientists will also learn how the jets interact with the dust particles and gas coma that is surrounding the nucleus, but which is only clearly visible at much greater distances from the comet (for example, take a look at the coma as seen through the ground-based VLT).

In addition to the jets, the new image also reveals surface features from the “dark-side” of the comet. Although this region is not yet illuminated directly – this will happen as the comet moves ever closer to perihelion in August this year – the diffuse light reflected from other areas allows a glimpse of what is to come.