Interstellar 2.0

Like the fascinating cigar-shaped ‘Oumuamua, which flew by in 2017, this bright object is also a comet, yet it cuts a very different shape in the sky.

The new object, dubbed C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), was first detected on 30 August by amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov.

About a week later, Marco Micheli from ESA’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre obtained images through the International Scientific Optical Network and performed several position measurements using data taken with the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii.

This data confirmed the object’s unusual orbit, which was first reported by NASA’s Scout system, a real time monitor of newly discovered asteroids and comets.

ESA is now analysing all available data, as well as planning more observations to further refine the object’s path through space.

Despite being monitored by many telescopes and astronomers around the globe, there is still some uncertainty in the path and the origin of this interesting object.

Like the unfolding story of ‘Oumuamua – first thought to be an asteroid then finally a comet – this looks set to be another exciting scientific investigation of an unusual visitor, helping boost our knowledge of solar system formation.

Between the stars

As the word suggests, an interstellar object is ‘between the stars’, roaming through space and no longer bound or ‘trapped’ in orbit about any specific star around which they formed.

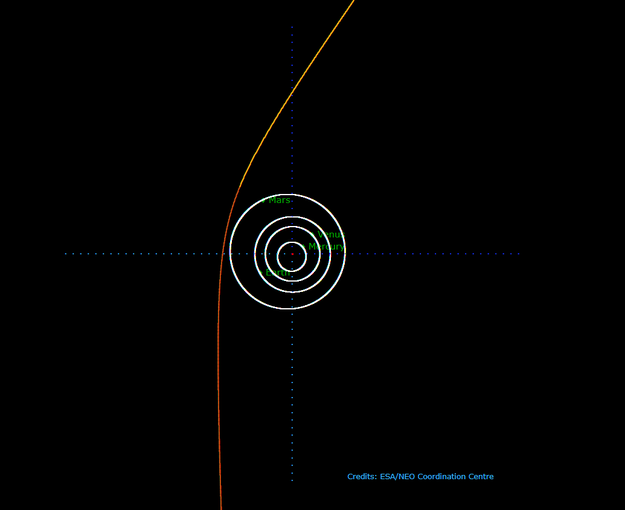

Astronomers can tell a lot about an object from the shape of its orbit, in particular its eccentricity – how much it is ‘stretched’.

Planets in near-perfect circular orbits around their star, Earth for example, have an eccentricity close to zero.

Comets and asteroids in orbit around a body with elongated paths are described as having an eccentricity of between zero and one, and objects with an eccentricity greater than one, ‘hyperbolic’ orbits, are interstellar.

Current observations strongly suggest that C/2019 Q4 is interstellar, its orbit being highly elongated with an eccentricity of about three.

However, we also know that the uncertainty in these early observations is high as they were taken as the object was near the Sun in the sky and close to the horizon – two factors that negatively affect the quality of observations.

Vitally, it also requires measurements taken over an extended period to really determine an object’s path, to understand where it has come from and where it is headed.

When a comet or asteroid is first detected, it is merely a tiny point of light. But over time, multiple observations allow astronomers to ‘draw an arc in the sky’, from which the object’s orbit can be extrapolated.

“We are now working on getting more observations of this unusual object,” says Marco Micheli of ESA’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre.

“We need to wait a few days to really pin down its origin with observations that will either prove the current thesis that it is interstellar, or perhaps drastically change our understanding”.

Dirty snowballs

We do know so far, that C/2019 Q4 is a relatively large active comet a few kilometres in diameter. It is expected to make its closest approach to the Sun in early December, coming within about 300 million km of our star.

At this distance it is not considered a near-Earth object (NEO) – a comet or asteroid travelling in a path that would see it come close to Earth – of which there are currently more than 20 000 known to date.

Comets are cold, fragile and irregular bodies made up of frozen gasses and grains of dust. Usually, they travel in highly elongated – or stretched – orbits around the Sun, spending most of their time far away at freezing temperatures but passing briefly by our raging star – and not always surviving the encounter.

If they pass close enough, the Sun’s radiation causes a comet’s volatile gases to ‘sublimate’ – going from solid ice to vapour gas in one step, taking with them small bits of solid material and creating enormous ‘tails’. Also known as the coma, these trails stream off in the opposite direction to the Sun, driven by the solar wind.

Comet interceptor

Had comet C/2019 Q4 entered our Solar System a few years later, it could have been a potential candidate for ESA’s ‘Comet Interceptor’ mission.

Comprising three spacecraft, Comet Interceptor's primary target will be to visit a truly pristine comet in the Oort cloud but could include an interstellar object as it begins its journey into the inner Solar System.

If confirmed as interstellar, as was ‘Oumuamua, the discovery of two such bodies in just two years may suggest that these objects are far more common than previously suspected.

This is an exciting prospect for the interceptor mission and adds to our understanding of the formation of our Solar System and others throughout the Universe.

Planetary defence

New near-Earth objects are constantly being discovered, some of which are added to ESA’s ‘risk list’and all of which are monitored by ESA’s NEO Coordination Centre, part of the Planetary Defence Office.

Find out more about the work of the Office, including the planned Hera mission to test asteroid deflection, here.