MU69 appears as a bi-lobed baby comet in latest New Horizons images

This is a textbook example of a contact binary. Binary means two objects, of course, and contact means that they’re in contact with each other. Separated binaries are very common in the solar system and especially common in the Kuiper belt. But how can a contact binary form? Is it even plausible for two mutually orbiting bodies to somehow come together so gently and just stick to each other while preserving their originally round shape over billions of years?

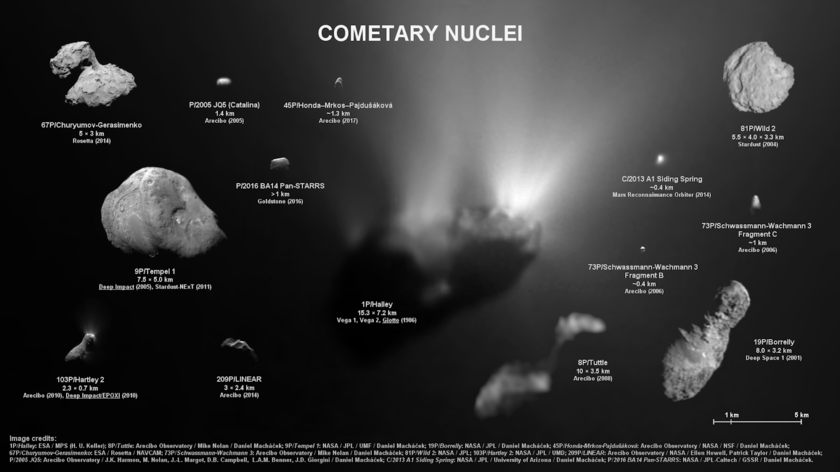

Solar system formation theorists have been considering this problem for a long time, because bi-lobed worlds are actually the commonest shape among cometary nuclei. The first comet we ever saw up close, 1P/Halley, has that shape. So do 19P/Borrelly, 103P/Hartley 2, and -- an extreme case -- 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the comet visited by Rosetta. Other comets imaged by radar seem to have that shape, too. Thanks to Daniel Macháček for this marvelous montage. Churyumov-Gerasimenko is in the upper left corner, in all its capybara-esque cuteness.

COMETARY NUCLEI IMAGED BY SPACECRAFT AND RADIO TELESCOPE, TO SCALE

Collage of all cometary nuclei imaged by spacecraft and planetary radars. When fully enlarged, resolution is 25 meters per pixel.

We don’t know for sure how any of this stuff formed from the solar nebula in the first place. One currently favored hypothesis is pebble accretion. I won’t go into it here. Augusto Carbillado wrote an excellent blog about the process of planetary accretion for us a few years ago, if you want to learn more.

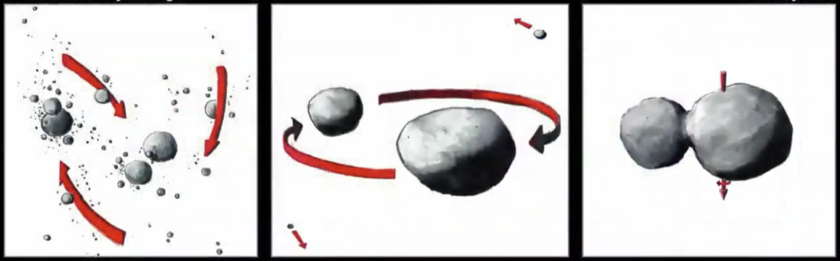

A recent paper by David Nesvorný, Joel Parker, and David Vokrouhlický that explains how 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko may have formed could also apply to MU69. Summarizing other peoples’ work, they wrote that the comet may initially have been a separated binary that formed when a clump of pebbles collapsed under its own gravity. Simulations show that this works physically, and moreover that it’s very common to end up with a binary pair where one object is about 75% the diameter (and therefore about half the mass) of the other. That ratio is common in the Kuiper belt, and is the ratio of the two lobes of 67P. Lo and behold, it doesn’t look far off of the value for MU69, either.

So how does a separated binary become a contact binary? One thing that needs to happen, obviously, is that the two components have to get closer together. In physics terms, their orbit needs to destabilize. Nesvorný and coauthors say the orbit could destabilize in several ways. Small impacts on either object could cancel out some of their orbital energy, allowing them to draw closer to each other over time. The same process might have the opposite effect on other binaries; random chance would separate some wider, while it would bring others closer. If the binary orbit was significantly tilted with respect to the plane of its orbit around the Sun, a kind of orbital dynamic called Kozai cycles could draw them closer together.

Nesvorný, Parker, and Vokrouhlický find that it’s quite possible to collapse binaries extremely gently. They touch at about 80 centimeters per second. That’s slower than human walking speed. I looked around for another creature (besides “a child”) that walks at 80 centimeters per second, and thanks to Michele Bannister I know that geckos climb vertically at 77 centimeters per second. So the two members of a contact binary collide with the speed of a gecko climbing a wall. (That’s adorable.)

FORMATION OF A CONTACT BINARY LIKE 2014 MU69 Binary systems formed when aggregates of pebbles accreted into separated binaries under the force of gravity. Eventually, the orbit destabilized and the two pieces came into contact at a very slow speed of 80 centimeters per second or so.

“For such low speeds,” Nesvorný et al. write, “impacts are expected to result in accretion of the binary components. This may happen instantly, during a single head-on collision, or after a series of grazing collisions. If the components have sufficient cohesion before impacts, the end result of this process should be the formation of a contact binary.”

How can they get closer together and then...just stick? If they start out as rubble piles, why don’t they just merge together into one, bigger, sort of spherical rubble pile? They probably would, if the whole process happened quickly. The paper posits that in order to keep this merger from happening, you need some time between the formation of the original, separated binary and the collapse of the binary, “a significant delay...possibly as long as ?10 Myr, during which the two components of a binary can gain the internal strength (e.g., by modest radioactive heating), and resist disintegration during their later assembly into a contact binary.”

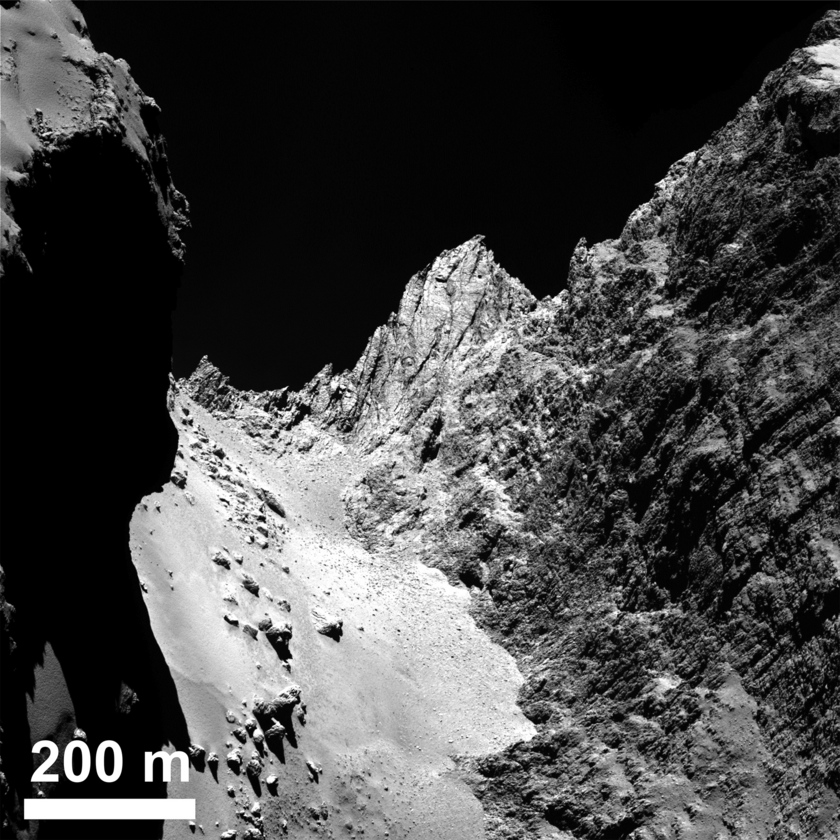

All of this would be very consistent with the appearance of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Its density is only half that of water, even though it’s mostly made of dust with only some ice -- its porosity has to be around 80%. Its two lobes have visible layers that don’t line up across the lobes, suggesting that they’re two bodies that formed by accretion and later stuck together.

LAYERS IN HATHOR The Hathor region of comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko exposes layers and fractures in one of the two cometary lobes, which now rise as a great cliff over the smooth, rubbly region of the neck, called Hapi.

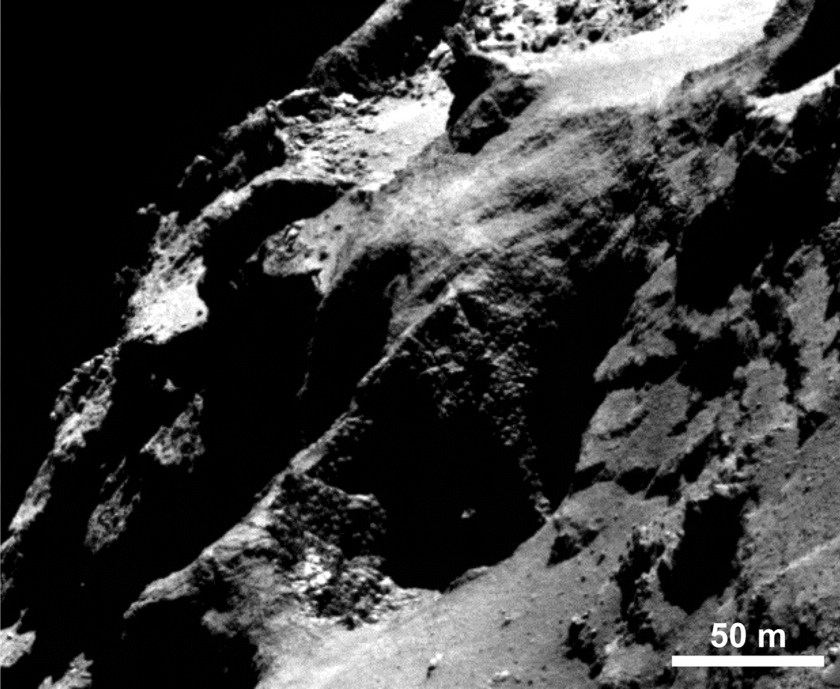

Very close up, Rosetta saw individual grains making up the structure of the comet. Were these the original meter-scale bodies that formed the initial rubble piles?

DINOSAUR EGGS OR GOOSEBUMPS IN A COMET CLIFF Close-up of a curious surface texture nicknamed ‘goosebumps’. The characteristic scale of all the bumps seen on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko by the OSIRIS narrow-angle camera is approximately 3 m, extending over regions greater than 100 m. They are seen on very steep slopes and on exposed cliff faces, but their formation mechanism is yet to be explained.

As for MU69 -- we’ll never see it as close as Rosetta saw 67P. But you can bet they’ll be looking for signs of its primordial accretion, especially layers and visible sub-objects, and signs of what happened when the two components initially booped together. This may not be easy; 67P’s layers and “goosebumps” are only visible because the comet’s passage close to the Sun is causing it to disintegrate rapidly. MU69 looks very much like what you would expect a comet seed to look like. MU69 will probably never become a comet -- but countless of its siblings have, and will again. Now, we have a baby picture of a comet.

Incidentally, writing this blog post has been a great excuse to go explore my archive of Rosetta images. While we’re waiting for New Horizons downlinks, please go enjoy Churyumov-Gerasimenko’s beauty.

By: Emily Lakdawalla