The great pit of Deir el-Medina

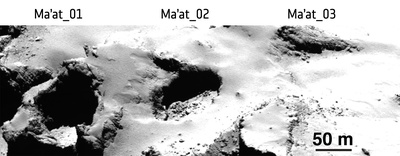

The target site is seen in the image below of three pits in Ma’at (first presented in a paper published in July 2015); Rosetta will target the smooth region between the pits labelled Ma’at 02 and 03.

The large, well-defined pit adjacent to the target site and identified in the image above as Ma’at 02 has now been named by the mission team as Deir el-Medina, after a pit in an ancient Egyptian town of the same name.

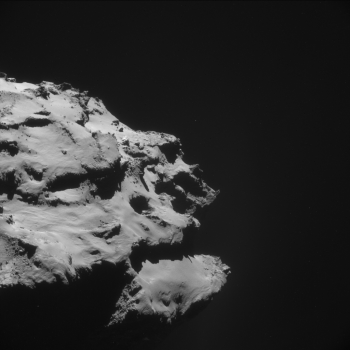

The Ma'at pits and surrounding region seen from 18 km on 8 October 2014. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

The pit bears resemblance in appearance to the pit in the Egyptian town that was home to many of the workers that built the pharaoh tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

The pit of Deir el-Medina, which measures about 50 m deep and 30 m wide, was originally dug by the town’s inhabitants in an attempt to find a local source water. They were unsuccessful, however, because the water table of the Nile River was much lower than it was possible to dig. Eventually the pit became the dumping ground for ‘ostraka’ the name given to discarded pieces of pottery that were used to record activities of daily life. These included, for example, short messages, love notes, medical prescriptions, receipts, recipes, and drawings.

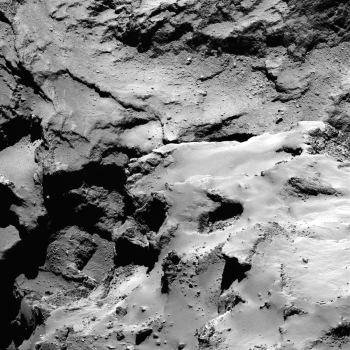

View of the Ma'at pits, including a nice view of the debris seen inside Deir el-Medina. The image was taken on 13 September 2014 from 30 km. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Just as the historical ‘debris’ that filled the pit gives historians insight into working life in that ancient town, so the rubble that can be seen inside Ma’at 02 is helping scientists to understand the history of Comet 67P/C-G.

Indeed, in addition to the rubble seen inside the pit, the walls also exhibit intriguing metre-sized lumpy structures called ‘goosebumps’. Rosetta scientists believe these could be the signatures of early cometesimals that merged together to create the comet in the early phases of Solar System formation. Rosetta’s descent over this region therefore offers the chance to capture close-up images of these important features.

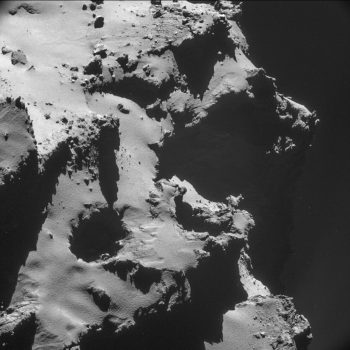

Single-frame NAVCAM image of the Ma'at pit region captured from a distance of 9.9 km from the centre of the comet on 15 October 2014. The image resolution is 84.6 cm/pixel and the size of the image is 866 x 866. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM – CC BY-SA IGO 3.0

In an earlier detailed study of Deir el-Medina and its neighbouring pits, scientists concluded that their differences in appearance may reflect their history of activity. While pits 1 and 2 are active, no activity has been observed from pit 3. The young, active pits are particularly steep-sided, whereas pits without any observed activity are shallower, have degraded rims, and seem to be filled with dust – and perhaps were active in the past. Middle-aged pits, like Deir el-Medina, tend to exhibit boulders on their floors from mass-wasting of the sides.

The pits – along with Rosetta’s target site – can be identified in many OSIRIS and NAVCAM images in the archive, affording many varied and spectacular views from different angles, and under a range of illumination conditions, as can be seen in some of the images accompanying this post.